Portrait photography is the process of taking a subject’s picture in an attempt to capture their personality. The element of consent separates portrait photography from every other type of photography involving people on the frame.

As Richard Avedon puts it, “A photographic portrait is a picture of someone who knows he is being photographed, and what he does with this knowledge is as much a part of the photograph as what he’s wearing or how he looks.”

As a headshot and portrait photographer capturing another human being’s personality or character — your subject’s “essence” — in a portrait takes mere hundredths of a second.

But portrait photography hasn’t always been that easy. In the late 18th century, the photographic process behind a single portrait took immense amounts of laborious, economically conscious efforts which greatly affected how portraits were done.

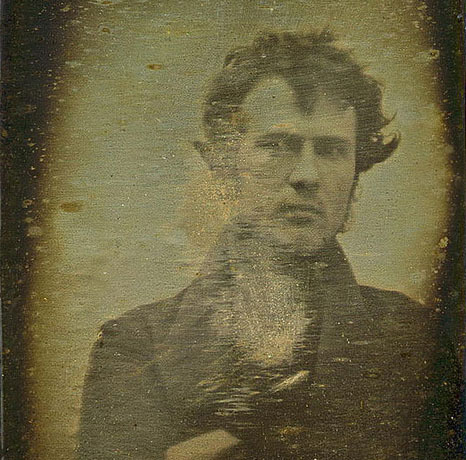

The First Photographic Portrait

Robert Cornelius’s Self-Portrait, 1839.

Getting painted portraits done used to be exclusive to families in the upper classes of society. That all changed when photography came into existence.

In 1839, Robert Cornelius shot the first successful portrait, a self-portrait (a selfie, no less), using the venerable daguerreotype.

Cornelius took advantage of the light outdoors to get a faster exposure. Sprinting out of his father’s shop, Robert held this pose for a whole minute before rushing back and putting the lens cap back on.

You see, shooting with the daguerreotype required between 3 to 15 minutes of exposure time depending on the available light — making portraiture incredibly impractical if not impossible.

But that’s not to say no one dared to experiment and use “Daguerreotyping,” as it was called, as an aesthetically satisfying form of creative expression.

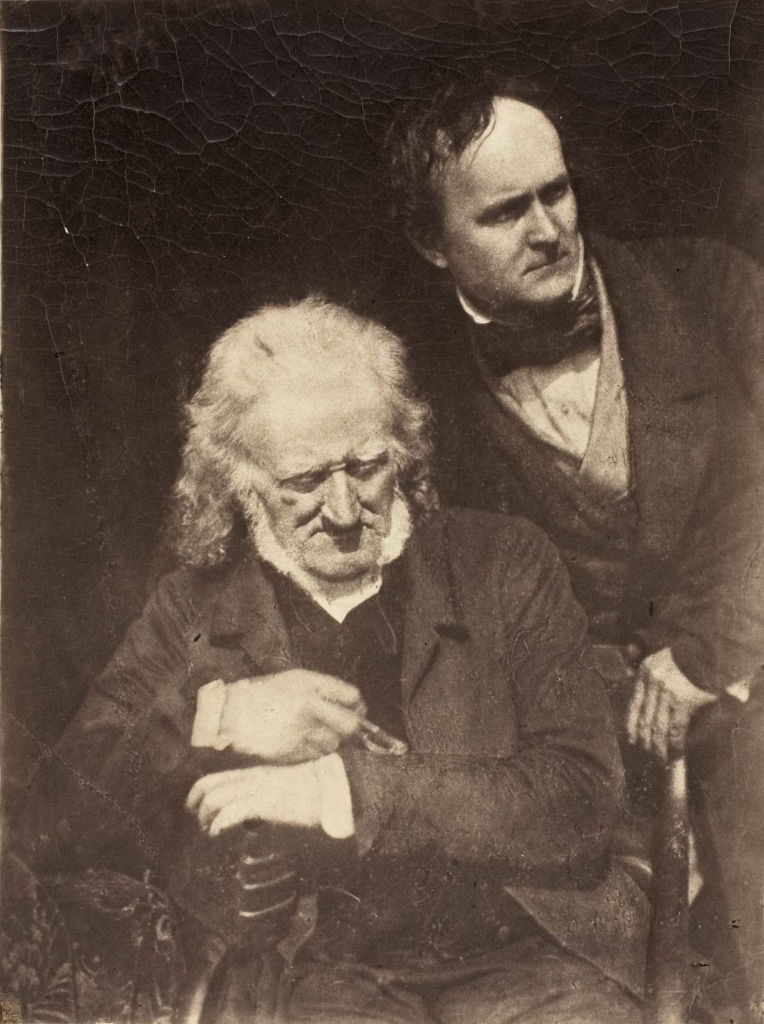

Scottish artists David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson incorporated heavy influences of Rembrandt painting styles, particularly intentional lighting, hand placement, and posing to their photos. The portrait below shines a welcome light of liveliness and grace against the stiff and cold subjects of the first daguerreotypes.

Portrait of Two Men, by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson

To improve exposure times, more sophisticated lens designs surfaced which allowed for greater light-gathering capabilities (suddenly, “faster” aperture lenses of today make a lot more sense). More light-sensitive chemical processes followed suit.

Leaps and bounds of technological advancements brought down 15-minute long exposure times to 20-40 seconds, to almost instantaneous captures.

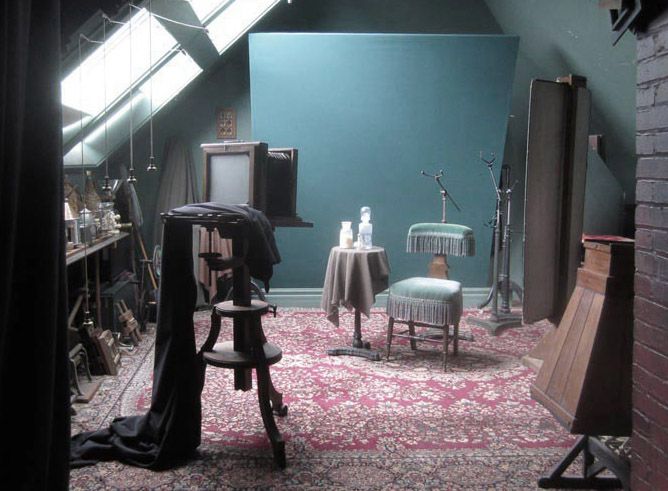

This led to the flourishing Daguerreotyping industry which spawned the first successful and profitable studios in Europe and the United States. By the late 1840s, every city had its own “Daguerrean artist,” — the first professional portrait photographers.

A 19th Century Studio

With the increasing development in photographic equipment, which brought down costs and broadened its accessibility to the public, droves of amateur photographers were born.

Many of which demanded that photography is finally recognized as an art form equal to painting. This was in response to the view that photography was a mere tool for recording reality (also known as straight photography). And so began the Pictorialism Movement of the 1860s.

Pictorialism and Naturalistic Photography

May Prinsep, as Beatrice Cenci (1866)

“Fading Away” by Henry Peach Robinson. A composite photograph made from 5 different negatives.

While the conventional need for portrait photography was often clinical and for documentation (profile shots etc.), the Pictorialists wanted to shift the focus from objective representation of subjects into a form of creative expression which highlights the subject’s beauty, composition, atmosphere and tonality.

To pictorialists, the photographer’s vision was front and center to the photographic process.

Staging scenes, compositing five different negatives into one image, soft-focus lenses — all were fair game if it added to the artistic value of a photograph.

The contending school of thought, Naturalistic Photography (or Straight Photography), however, maintained a strong commitment to representing objective reality with unaltered photos.

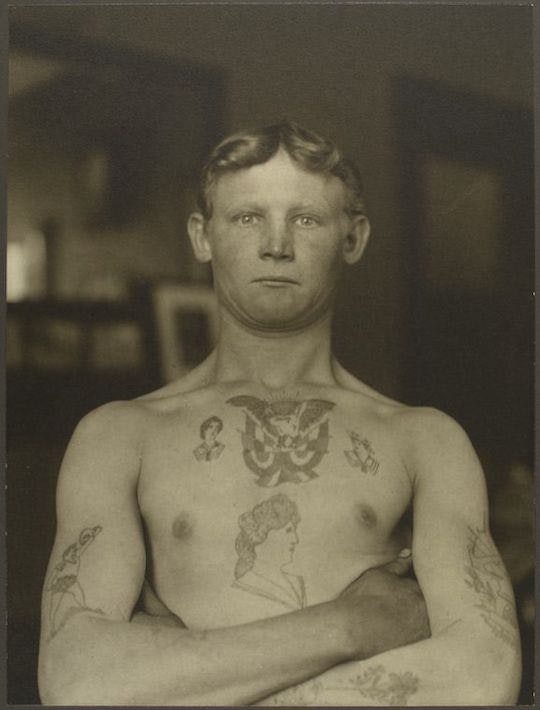

German Stowaway by Augustus Frederick Sherman, 1905

Peter Henry Emerson was a proponent of naturalism. In his book, Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art (1889), Emerson claims that “a photograph should be direct and simple and show real people in their own environment, not costumed models posed before fake backdrops or other such predetermined formulas.”

It is however worth noting that Emerson later withdrew his opinion about Naturalistic Photography being the only valid way to create art through photography.

Nonetheless, both schools of thought have bled on to modern times and undeniably influenced generations of portrait photographers.

Marilyn Monroe by Richard Avedon, 1957

Pictorialism and Naturalistic photography inevitably evolved and spilled over each other (how much editing is okay?) throughout the history of portraiture.

For every photojournalist weaving his way through riots, a fashion photographer is lining up the perfect cover shot for this month’s issue of Vogue.

Peter Henry Emerson Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art (1889),

It’s interesting to know how portrait photography has evolved throughout the years. Not long ago, my uncle mentioned he’d like to get a professional photographer to do some portraits for his business campaign. I think he’d benefit from reading your information since he’ll need to find a photographer with a vision.

If you use her photograph, you have to credit her:

The photograph labelled “May Prinsep, as Beatrice Cenci (1866)” is by Julia Margaret Cameron